Taking time away from your opponent: The key to on-court success

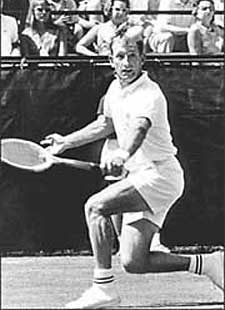

Fred Perry used an attacking style to dominate world tennis until 1936.

Fred Perry used an attacking style to dominate world tennis until 1936.

One of the most important aspects of the game which club players can learn, by observing the pros, is the ability to take time away from an opponent. This skill, combined with the ability to defend or buy time when they are forced into a weakened position, are the two major ingredients to becoming a successful pro or a success at any level of the game. This understanding has done more to develop technique, movement patterns and tactics than anything else. Let's examine how it has impacted tennis development over the years.

The basic tactic of coming to the net is the ultimate tactic for taking time away from an opponent. Top players in the 1920s and 30s began to venture forward as a way of finishing off points. This developed quickly, with the rule change in the 1960s allowing players to land inside the baseline after serving, which opened up the tactic of serve and volley as a major and dominating tactic.

Fred Perry dominated world tennis until 1936, through a combination of aggression and his acute understanding of the psychology of match play.

It was one of the local amateur coaches that encouraged Fred to adopt a style of play that utilised this natural strength to catch the ball early on the top of the bounce and strike firmly, while at the same time moving forward to attack.

Taking the ball on the rise and playing slice (mostly with the backhand) helped players move through the ball with a natural flow when approaching the net. This cut down time while retaining control and accuracy. Defending with slice is accurate and slows the point down. Using slice to keep the ball very low over the net in the face of an advancing opponent, forces the opponent to volley up thus giving the defender more time to recover.

The evolution of topspin

The evolution of topspin

The development of topspin was a major step forward in the effort to cut down time. Topspin allowed players to hit harder and higher over the net, creating good length with less risk.

Studies have shown that a ball can lose up to 50% of its speed after the bounce, so length is an important component of taking time away from an opponent. Conversely, topspin also helped players to defend better, by giving them the opportunity to hit high enough over the net to buy time, yet hard enough to prevent the opponent from moving in for the easy volley.

Although others, like Little Bill Johnston in the twenties, had used topspin before, Laver ushered in a wave of heavy hitting topspin practitioners in the 1970s such as Bjorn Borg and Guillermo Vilas, especially on the backhand side. The stroke became basic after the ‘Rocket’

Open-stance forehand

Movement and technique advanced again on the forehand when open-stance forehands began to dominate the world game.

The ability to hit from an open stance negated the need to retreat as much from pace and length. It allowed players more time and space than turning side on.

Also, hitting from an open stance cut down recovery time by saving a step or two.

Although the game went through a period of height and spin which effectively was defensive and counter-punching (Borg, Vilas, and Wilander) verses the flat attacking ground-strokes of Connors, the defenders were able to attack the short ball with accuracy and topspin that really jumped off the court.

Bjorn Borg in fact was highly influential in changing tennis grips on the forehand side to semi-western and full western, as players began to realise the advantages of topspin and open-stance forehands. He was able to adapt this clay-court style to other surfaces, proving early critics wrong by winning 5 Wimbledons and he also put an end to ‘nonsense’ that was being spouted, which suggested that playing with this extreme grip he would injure his arm and not sustain this form of play for very long.

Later John McEnroe, who instinctively understood cutting away time like none other before him, was able to take the heavy spin created by Borg and the other baseliners on the rise and flatten it out to approach the net giving them less time to set up for passing shots.

The desire to find a way to take away time from the height and spin merchants, who were all excellent movers, began to formulate with a player who does not in my opinion get the credit he deserves - Ivan Lendl.

Lendl's ability to take the ball at a higher point and flatten out the spin was the beginning of the end for the pure height and spin players.

Also, he, along with Martina Navratilova, began to change the physical training regimen and the strength of players, so that they had the power and stamina to attack the ball for hours.

Arguably, Lendl could be considered the first true tennis professional! His single-minded approach and dedication to winning saw him pioneer changes in diet and physical training methods and his level of professionalism has now been adopted as the norm for players who want to win.

Everything from physical conditioning, mental toughness, equipment specifications, match preparation, player scouting and awareness of tennis history was employed to the fullest by Ivan Lendl.

Lendl's style coincided with the massive surge forward in racquet technology. The bigger heads and lighter frames that manufacturers were developing allowed for easier power.

I strongly dispute, however, the notion that tennis would not have advanced in the same direction without this technological improvement. Although it would have most likely happened at a slower rate and not quite as ferociously.

The attacking game

There have always been the out-and-out attackers who cut down time by going to the net as much as possible and therefore served and volleyed almost exclusively on both serves.

During the 60s and early 70s, this style largely dominated tennis. This was because of the desire of top players to win Grand Slams and since 3 of the 4 were on grass of dubious quality, apart from the French Open, this was the best approach.

John Newcombe used just such an attacking game to win three Wimbledons (1967, 1970, 1971), U.S. Open titles in 1967 and 1973, plus two Australian titles in 1973 and 1975. Although he had an excellent slice-backhand approach, his game was largely built around his serve, volley and forehand.

Boris Becker took this approach to the game to a new level. He combined the power off the ground of Lendl with aggressive net play. He also began to return open stance off the backhand and that allowed him to threaten serves more by standing in closer, thus cutting away the server's response time. As obvious as it seems now, it is a wonder that open-stance backhands off deep balls only began to emerge strongly in the current era.

Andre Agassi pioneered the drive volley into mainstream technique as a way of taking balls out of the air when floated. This allowed him to generate far more pace than a conventional volley and play further from the net but still take away an opponent’s time with this tactic.

Andre was also part of the Bollettieri revolution which emphasised the away forehand, which was more powerful than hitting backhands, again taking away time from his opponent. Not only because of the added power but also because of the disguise this method of play offered. Andre combined the power of Becker and the earliness of McEnroe.

Open-stance backhand

Venus and Serena Williams have certainly moved the game forward by almost exclusively using the open-stance backhand for any deep ball.

Much in the way Lendl and Martina Navratilova did in the 70s, they have paved the way forward for the women to become much more physical and aggressive off the ground. This is unusual as it is probably the first time that women have pioneered a change in the way tennis is played.

Perhaps no one in the modern era understood the value of time and variety of pace better than Pete Sampras. Sampras was able to combine much of what came before him and mould it into the blueprint for the modern all-court player.

The question we need to ask is what could possibly be the next step forward in technique, based on the premise that technique develops because of the desire to cut down an opponent's time. I believe tennis is moving towards an attacking all-court game, where players will constantly be on the lookout for opportunities to sneak in and take the ball out of the air, either with drive volleys or conventional volleys.

With the power at the command of today's players, it will become increasingly important to understand time and to be able to play any stroke or spin, either with closed or open stance with competence. Already it is hard to find top players who cannot achieve most of this.

One need only to look at the change in the way the Spanish are playing. Moya, Costa and especially Juan Carlos Ferrero are venturing to the net more often and it is not unusual to see them serve and volley a pressure point. Hewitt is also beginning to adjust and they are all moving closer to the Federer/Roddick style of play than the other way.

Throughout all the eras, top players adjust to changes which allow them to bridge eras, as the game evolves to compete with new stars. Those that cannot adjust are quickly left behind.

Summary

In summary the developments in movement, tactics and technique are as follows:

1 .Fred Perry approaches the net often and begins a more aggressive style of play.

2. The 50s, 60s and 70s are dominated by serve and volley players such as Gonzalez, Hoad, Emerson, Rosewall, Newcombe, Ashe and Smith, in their pursuit of Grand Slams on grass.

3. Rod Laver stands out from the rest in his use of topspin, especially off the backhand side and starts to move tennis in a new direction.

4. There is a gap, where players begin to hit harder but still play either from the back fairly flat, or very flat in the case of Jimmy Connors, or serve and volley in the conventional way. The two-fisted backhand begins to emerge as a viable option for the mainstream.

5. Bjorn Borg emerges as the first player to truly make full use of topspin, the open-stance forehand, a topspin two-handed backhand with semi/full western grips at the highest level. The game moves quickly towards topspin.

6. McEnroe and Connors can still compete with the topspin kings by taking the ball early: McEnroe getting to the net quickly and Connors cutting in for the kill, but generally topspin dominates.

7. Enter Ivan Lendl, with new levels of fitness and strength, able to mix spin with a flatter power on both wings. He also begins to dominate with the forehand from anywhere on the court.

8. Boris Becker and Stephan Edberg combine the power of Lendl with powerful net-play and the beginnings of the all-court power game.

9. Agassi and Courier take the lead from Lendl (schooled in the Bollettieri Academy) and play as few backhands as possible, as they use power and spin to dominate with forehands from the ad-court. They add in the drive volley as a way of killing off the floating ball.

10. Sampras develops along similar lines to Becker, but is able to take the ball earlier at times and develops an excellent backhand down the line, to counter the Agassi/Courier style of play. Sampras becomes the model for the emerging all-court power player.

Tennis will always have those who prefer going to the net versus those who prefer to attack from the baseline and wait for opportunities to sneak in for the volley or drive volley, but I do not think an out-and-out baseliner will play at the top of the men’s game ever again. The women will follow suit but without the same explosive power, more baseliners will survive.

by David Sammel

Pictures used in this article are courtesy of TennisOne